Undoubtedly, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) is the most impactful engagement framework in the history of China’s relations with Africa. Its creation jumpstarted the deepening China-Africa relations being witnessed today. However, its success overshadowing every other existing multilateral forum with Africa has led to the often-wrong conception of the origin and true nature of FOCAC.

FOCAC has been widely construed as a Sinocentric, Chinese self-interested creation and a grand foreign policy machination tool dictated and imposed by China as the dominant actor to serve its interests in Africa. Some have even gone to the extent of construing the forum as a place where African leaders go for ‘photo-ops’ with Chinese leaders in exchange for handouts. The truth is that contrary to the widespread assumption, FOCAC is a joint initiative by China and Africa. In fact, the idea of a framework to guide China-Africa relations was first mooted by African countries. Consequently, an agreement by both China and African countries led to the birth of FOCAC as a bargained institutional framework for shared impacts. Today, it has grown from just an avenue for diplomatic discussions to a platform for exchanging ideas and experiences to advance shared development goals.

The Genesis of FOCAC

With the increasing interaction between Chinese and African leaders in the late 1970s made possible by China’s opening-up policy, diplomats and leaders from some African countries floated the idea of a guiding framework for the increasing China-Africa interactions.

It must be noted that African countries were familiar with such a proposed framework, having participated in the Japan-led Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) as early as 1993. However, neither side took steps to materialize the idea until the same idea was rehashed in 1999 by the then-foreign minister of Madagascar (Lila Ratsifandrihamanana) to the then-Chinese Foreign minister (Tang Jiaxuan).

China responded constructively after much consideration of the various proposals. In taking up a leadership role, the then-Chinese President (Jiang Zemin) wrote to African leaders in the same year to formally suggest convening a multilateral conference between China and African countries. The suggestion became fruitful with an inaugural meeting in Beijing in October 2000. The meeting, dubbed a ministerial conference, was successful, with delegations from about 44 African countries—including over 80 ministers and a handful of African leaders.

At the maiden meeting, the principal agenda was to consolidate the common interest between China and African countries by developing an institutionalized framework. The outcome was adopting a treaty entitled: “Beijing Declaration of the FOCAC.”

This treaty declared the formation of FOCAC as a China-Africa cooperative platform for common development. As of today, eight (8) meetings have since been held triennial alternately between China and African countries (see Table 1).

It has also been upgraded from a ministerial conference to a full-fledged Head of State summit. The 2018 summit was the largest in the history of China-Africa relations, with delegations from all African countries except eSwatini. In fact, it assembled twice as many African leaders as the 73rd United Nations General Assembly held two weeks later.

| Edition | Year held | Type | Location |

| 1st (FOCAC I) | 2000 | Ministerial conference | Beijing, China |

| 2nd (FOCAC II) | 2003 | Ministerial conference | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia |

| 3rd (FOCAC III) | 2006 | Head of States summit | Beijing, China |

| 4th (FOCAC IV) | 2009 | Ministerial conference | Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt |

| 5th (FOCAC V) | 2012 | Ministerial conference | Beijing, China |

| 6th (FOCAC VI) | 2015 | Head of States summit | Johannesburg, South Africa |

| 7th (FOCAC VII) | 2018 | Head of States summit | Beijing, China |

| 8th (FOCAC VIII) | 2021 | Head of States summit | Dakar, Senegal |

Table 1: List of FOCAC summits between 2000–2023 (Sources: Sibiri, 2021).

“Digital Roots in Africa”

China’s digital influence in African countries predates the Digital Silk Road initiative, particularly in the telecommunications industry with firms such as Huawei and ZTE. The implementation of Chinese companies in this specific area is a consequence of the continent’s telecommunications revolution, which began in the 1990s.

Given their competitive pricing, cost-effective equipment and solutions, and government-subsidized funding, Chinese companies have been able to dominate the market in a great number of African nations. They have massively contributed to the development of key telecoms infrastructure, from optical fiber backbone networks to “last-mile solutions”.

In the past few years, the telecommunications sector has experienced considerable advances, following the rapid development in the use of mobile telephony and internet technology. Chinese firms have been committed to revamping the industry, actively engaging in upgrading activities, and providing new solutions. In 2020, 46% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population had a mobile subscription, and estimates indicate that this number is expected to reach 50% by 2025.

Levels and Mechanism of Decision-making within FOCAC

Regarding decision-making, FOCAC functions at three levels of interactions in descending order.

- Decision at the first level occurs during the triennial summits. At the highest level, the decision involves direct interactions between Chinese and African leaders, presenting the outcome as treaties and policy actions.

- Second-level decision-making involves interaction between Chinese and African senior officials and/or ministers. Meetings at this level are organized twice every three years. These meetings aim to discuss and agree upon draft agendas for the head of states’ summits, prepare progress reports of previous agreements, and decide on other follow-up activities.

- The third level involves engagement between Chinese and African diplomats. Meetings at this last level are held bi-annually to seek ideas through consultation and feedback at all conceivable levels.

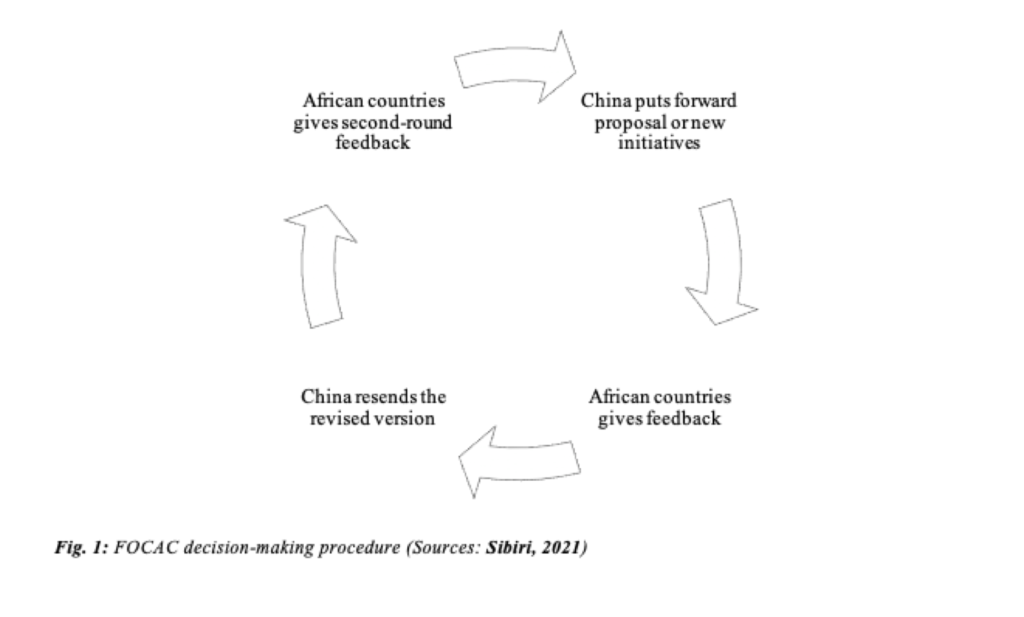

The implication of the above level of the decision-making process is that although China takes an active leadership role in implementing policies, decision-making within the framework involves a multi-layered and consultative process. As exemplified, multi-levels of consultation and feedback processes between China and African stakeholders ensure that all major decisions and policy objectives announced within the framework are mutually deliberated and agreed upon.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, for instance, a proposal from China goes through a series of consultation and feedback processes before reaching a consensus or otherwise. The same process applies to a proposal from African countries.

In addition to the three levels, several other engagement platforms have been established within the framework to facilitate exchanges among both governmental and non-governmental levels at all levels. These establishments include the China-Africa Joint Research and Exchange program, the think tanks forum, and the People’s Forum.

Concluding Remarks

As established in theories of institutional formation, institutions may be formed either from a negotiation (bargaining to form an institution) or non-negotiated (spontaneously or imposed by dominant actors).

FOCAC, as we understand from the above, is a product of mutual agreement and joint initiative. It is thus fair to be construed as a bargained institution as opposed to a Chinese creation and machination.

As a jointly initiated institution, FOCAC involves several decision-making processes through which common interests and ideas are aggregated, deliberated, and pursued. The success of the FOCAC (compared to the now multitude of Africa+1 forums) can be attributed to both parties’ commitments—particularly China’s active leadership role. China’s leadership role is critical because the role of leadership in institutions’ success arising from institutional bargaining is critical to its success, as the absence of such leadership will lead to its failure.

Written by: Dr. Hagan Sibiri, Senior Research Fellow, ACCPA